At the risk of appearing like I’m trying to out-geek the Shakespeare Geek, here’s another list.

You’ve seen my top 25 favorite plays and my top 25 favorite scenes (then expanded to 50). Here are my top 50 favorite characters (or groups of characters) from Shakespeare’s plays at the present moment. Enjoy! And feel free to add to the conversation, especially if I’ve left some of your favorites out!

50. The Nurse (Romeo and Juliet) – The play may be a tragedy, but the Nurse is one of the great comic roles in Shakespeare.

49. The Duke of York (Richard the Second) – The remaining son of Edward III is so loyal to the King, he’ll turn in his own son as a traitor.

48. Sir Toby Belch (Twelfth Night) – Think Falstaff without the good manners. Half the time he’s plotting; the other half he’s drunk.

47. The Prince of Morocco & The Prince of Arragon (The Merchant of Venice) – It’s hard to tell which of these two suitors to Portia is more unsuitable, or more hilarious.

46. Dogberry (Much Ado About Nothing) – The muddled constable of the watch who bumbles his way into uncovering the evil plot!

45. Helena (All’s Well That Ends Well) – I’ll never understand what a quality woman like Helena sees in a loser like Bertram. Sigh.

44. Richard the Second (Richard the Second) – Too much philosopher, not enough king. But divine right is divine right. Isn’t it?

43. Philip the Bastard (King John) – When you’re already a bastard, who cares what people think of you? Certainly not Philip.

42. Polonius (Hamlet) – He may be a rash, intruding, doddering old fool, but his madness has a method to it. I think.

41. Beatrice and Benedick (Much Ado About Nothing) – You can’t have one without the other. Sharp banter hiding a deep affection – very cool.

40. Portia (The Merchant of Venice) – Unlike some love interests, Portia is actually worth the winning, and not just for her money.

39. Puck (A Midsummer Night’s Dream) – The mischievous sprite who doesn’t mind helping mortals at times, as long as it’s funny.

38. Mercutio (Romeo and Juliet) – The madcap kinsman to the Prince is a grave man when caught between the two houses.

37. Lucio (Measure for Measure) – This guy is a riot from beginning to end, but slandering the Duke to his disguised face rules.

36. Marc Antony (Multiple plays) – His funeral oration is a masterpiece, but his most powerful line? “I am dying, Egypt, dying.”

35. Viola (Twelfth Night) – Her disguise-as-a-boy plan plunges her in over her head, but she handles it all with grace.

34. Brutus (Julius Caesar) – This was the noblest Roman of them all, deeply conflicted and ultimately his own undoing.

33. Cloten (Cymbeline) – Proud, arrogant, foolish, entitled, and a bully, Cloten is nothing but a suit and a title. Fun!

32. The Earl of Kent (King Lear) – Deeply loyal to the King who has banished him, Kent has something to teach us all.

31. Malvolio (Twelfth Night) – He didn’t really deserve what he got in the play, but he is a Puritan, after all.

30. Jacques (As You Like It) – He’s probably bipolar, but he’s a deep thinker and a keen observer of the human condition.

29. Caliban (The Tempest) – Caliban’s antics are a lot of fun, but I’m more interested in his backstory and its meaning.

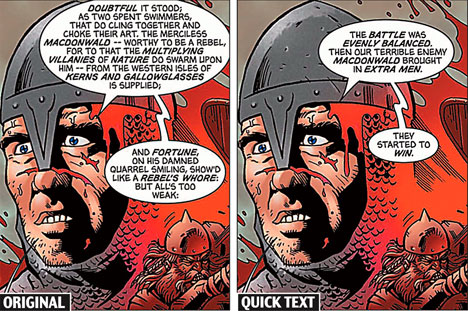

28. The Weird Sisters (Macbeth) – Do you think the three witches predict the future? Or do they cause it?

27. Tranio (The Taming of the Shrew) – A servant, who we mostly see playing gentleman. At the end, he’s back to waiting tables.

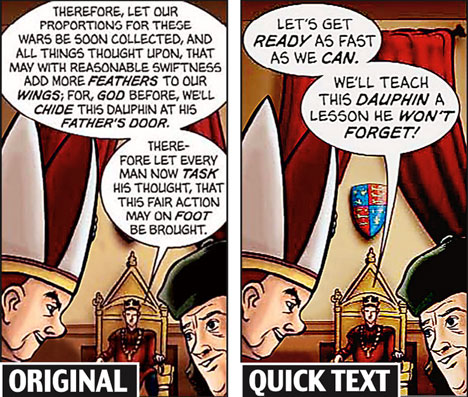

26. Lewis the Dauphin (Henry the Fifth) – We’re shown Henry’s suitability to be the next French king by seeing a weak Dauphin.

25. Isabella (Measure for Measure) – After all she’s been through, the Duke gives her one final impossible test. She passes.

24. Petruchio & Katherine (The Taming of the Shrew) – When an irresistible force meets an immovable object, somethin’s gotta give…

23. Emilia (Othello) – She’d make her husband a cuckold to make him a king, but won’t cover for his wickedness.

22. Iachimo (Cymbeline) – This “Little Iago” is clever and dishonest, and starts up way more trouble than he means to.

21. Enobarbus (Antony and Cleopatra) – A loyal soldier who can’t support Antony’s self-destructive course, and dies of shame.

20. Goneril & Regan (King Lear) – The wicked ones turn on their father, their husbands, their sister, and finally, each other.

19. Jack Cade (Henry the Sixth, Part Two) – This rough-hewn pretender to the throne would abolish money and kill all the lawyers.

18. Helena (A Midsummer Night’s Dream) – My heart just goes out to Helena, who is such a sweet person and gets rotten treatment.

17. Prospero (The Tempest) – The Duke of Milan, and wise old master of knowledge, books, and the elements of nature.

16. Hamlet (Hamlet) – The melancholy Dane helps us understand that murky place between thought and action.

15. Queen Margaret (Multiple plays) – With an amazing character arc that spans four plays, Margaret puts the “It” back in bitch.

14. Rosalind (As You Like It) – Let’s face it – Rosalind carries the whole plot on force of personality. We like her, so it works.

13. Macbeth (Macbeth) – From noble warrior to homicidal maniac, Macbeth experiences an incredible transformation.

12. Bottom (A Midsummer Night’s Dream) – The megalomaniac actor! We can all recognize him, but do we recognize ourselves in him?

11. Cleopatra (Antony and Cleopatra) – She’s a strong, empowered woman who’s not above using sex as a political tactic.

10. Edmund (King Lear) – A charming villain – all honor on the outside, and evil on the inside. What a bastard!

9. Othello (Othello) – A complex and passionate character, who loved (and trusted) not wisely, but too well.

8. Sir John Falstaff (Multiple plays) – A drunk, a theif, a liar, a glutton, and a pure hedonist. And those are his good points.

7. Duke of Gloucester/ Richard the Third (Multiple plays) – Since he cannot prove a lover, he is determined to prove a villain!

6. Shylock (The Merchant of Venice) – The Jewish moneylender may be the villain, but Shakespeare shows us his human side.

5. King Lear (King Lear) – Is dying the worst thing that can happen? What about having it all and watching it fade?

4. Prince Hal/ Henry the Fifth (Multiple plays) – Shakespeare traces England’s great hero from his wayward youth to his victory in France.

3. Lady Macbeth (Macbeth) – An equal partner in evil to Macbeth, and a force to be reckoned with. But then she breaks.

2. The Fool (King Lear) – The Fool balances that fine line between jesting clown, and sharp commentator on events.

1. Iago (Othello) – The hands-down, pure evil incarnate, puppet master general. But why does he do it?