Shakespeare Memes

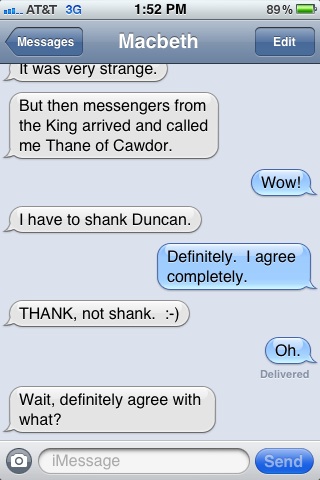

Tuesday, April 23rd, 2019Happy 455th Birthday to Shakespeare!

In honor of the occasion, I present… Shakespeare Memes!

Happy 455th Birthday to Shakespeare!

In honor of the occasion, I present… Shakespeare Memes!

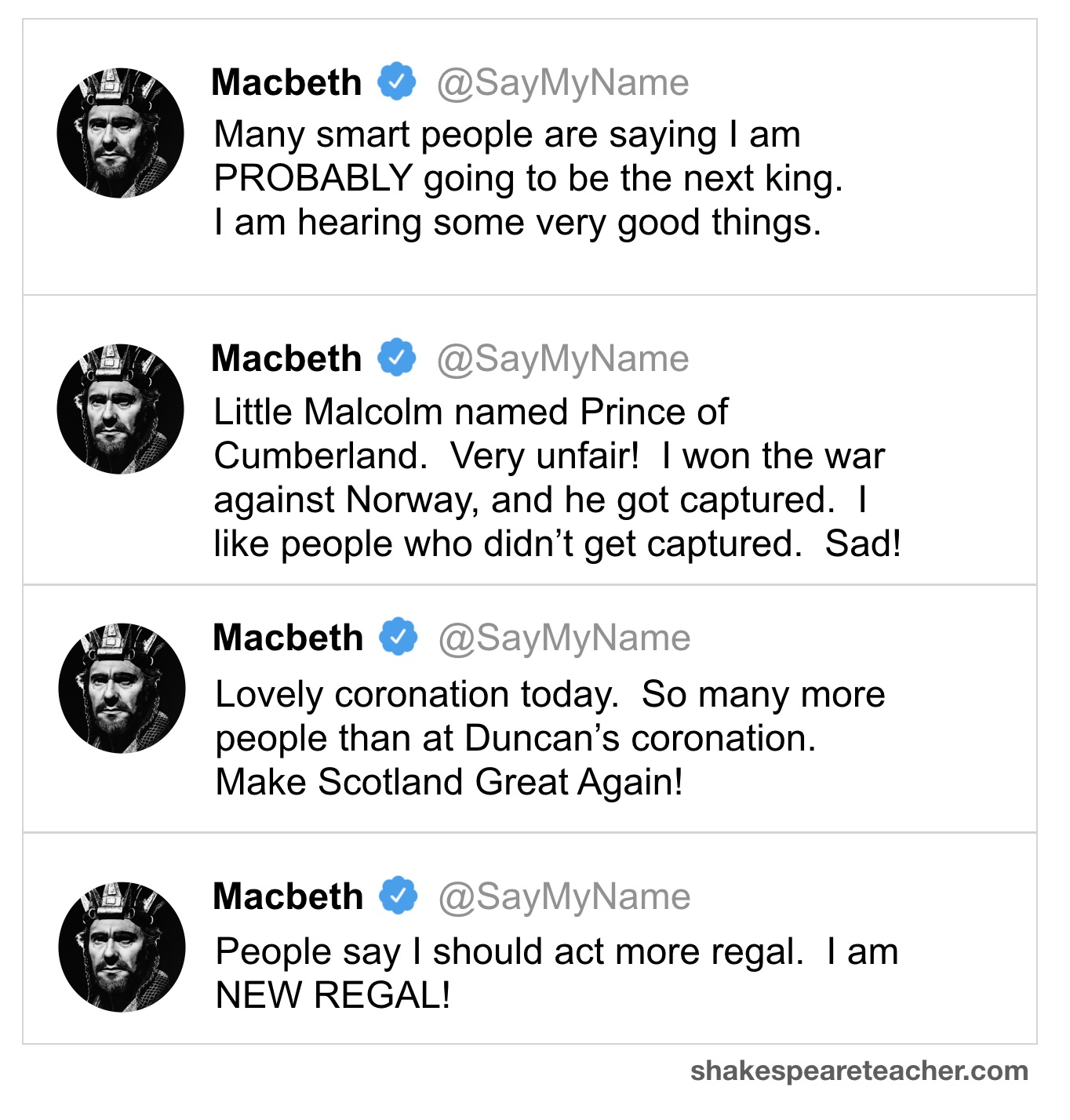

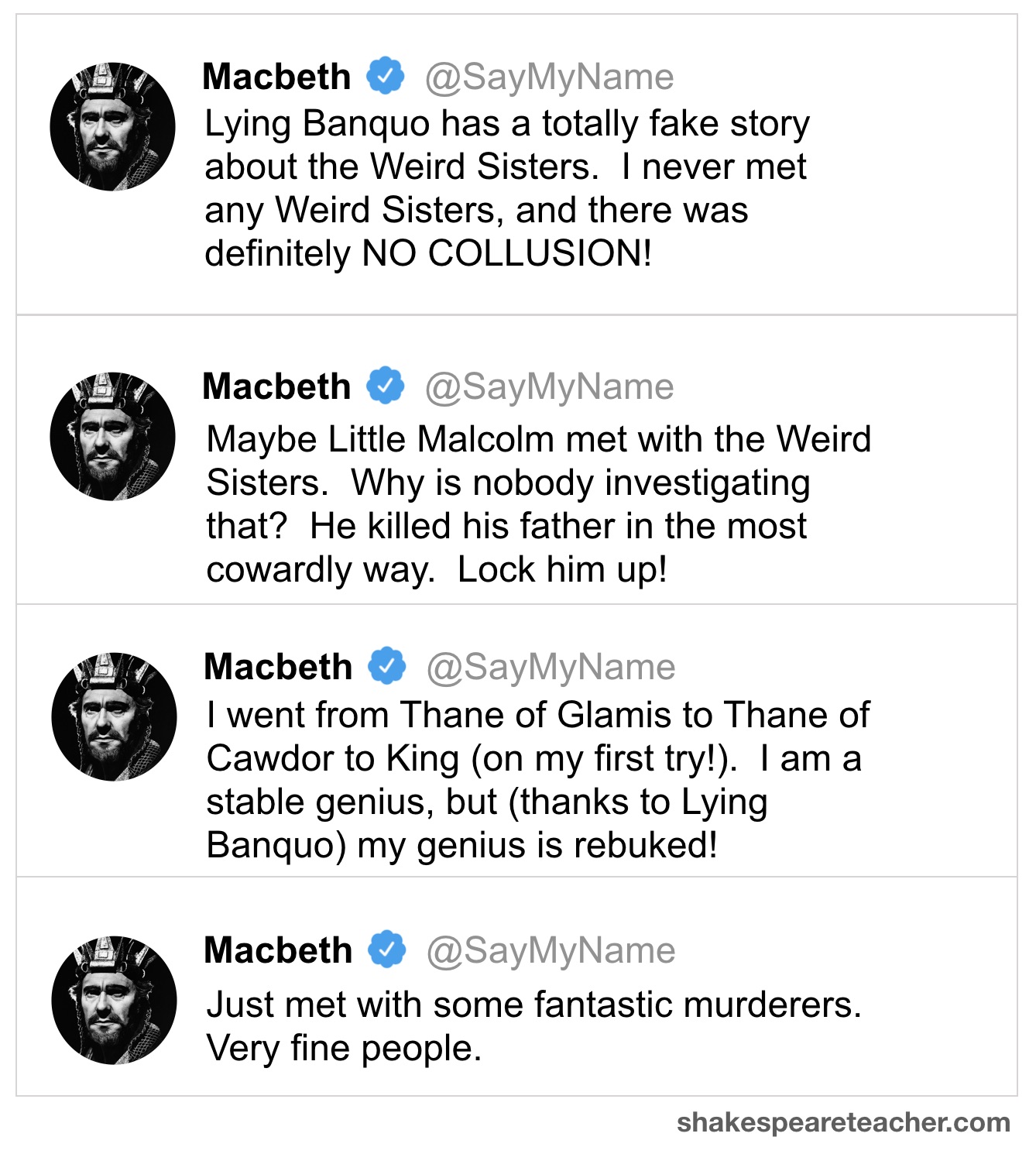

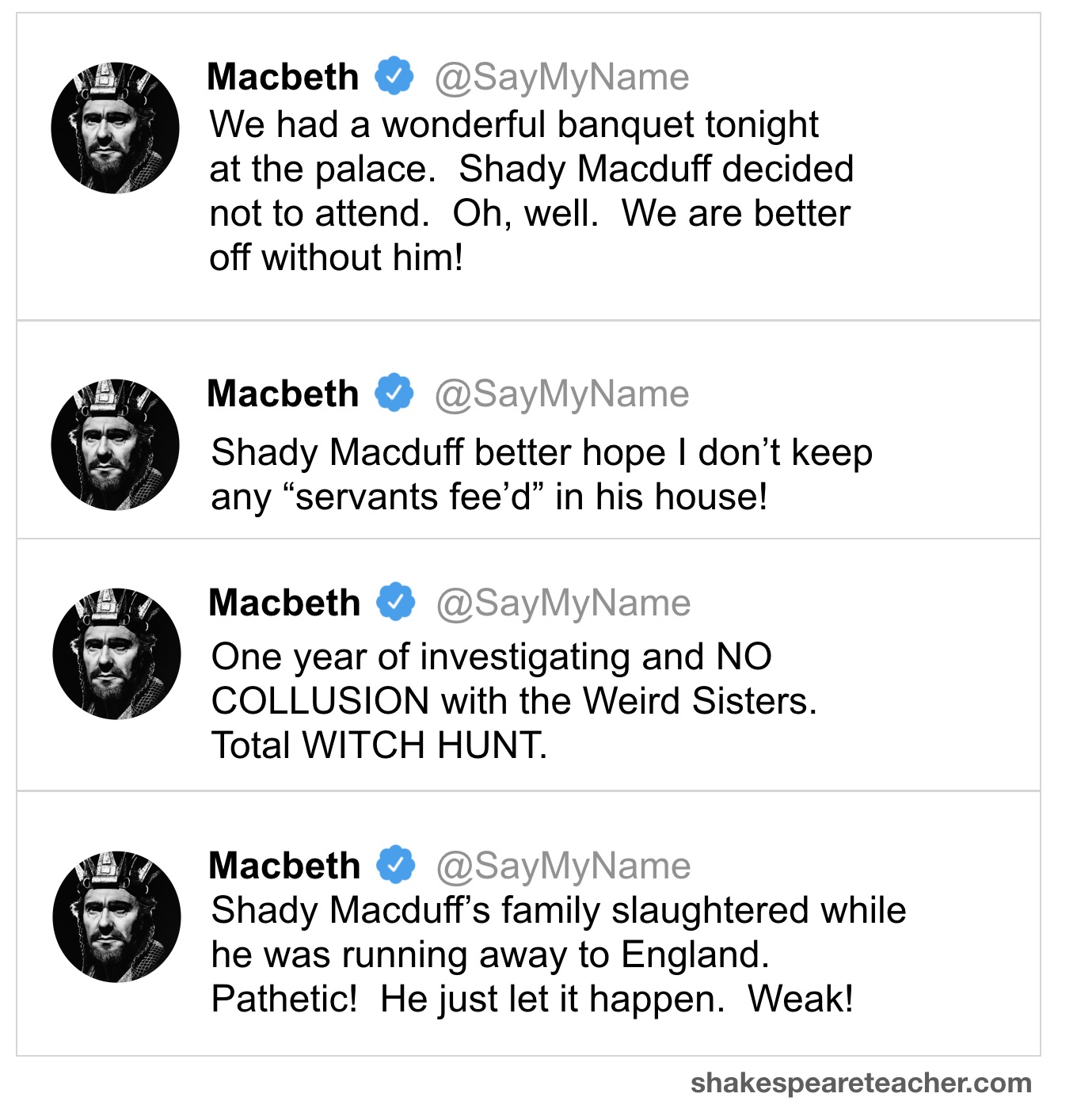

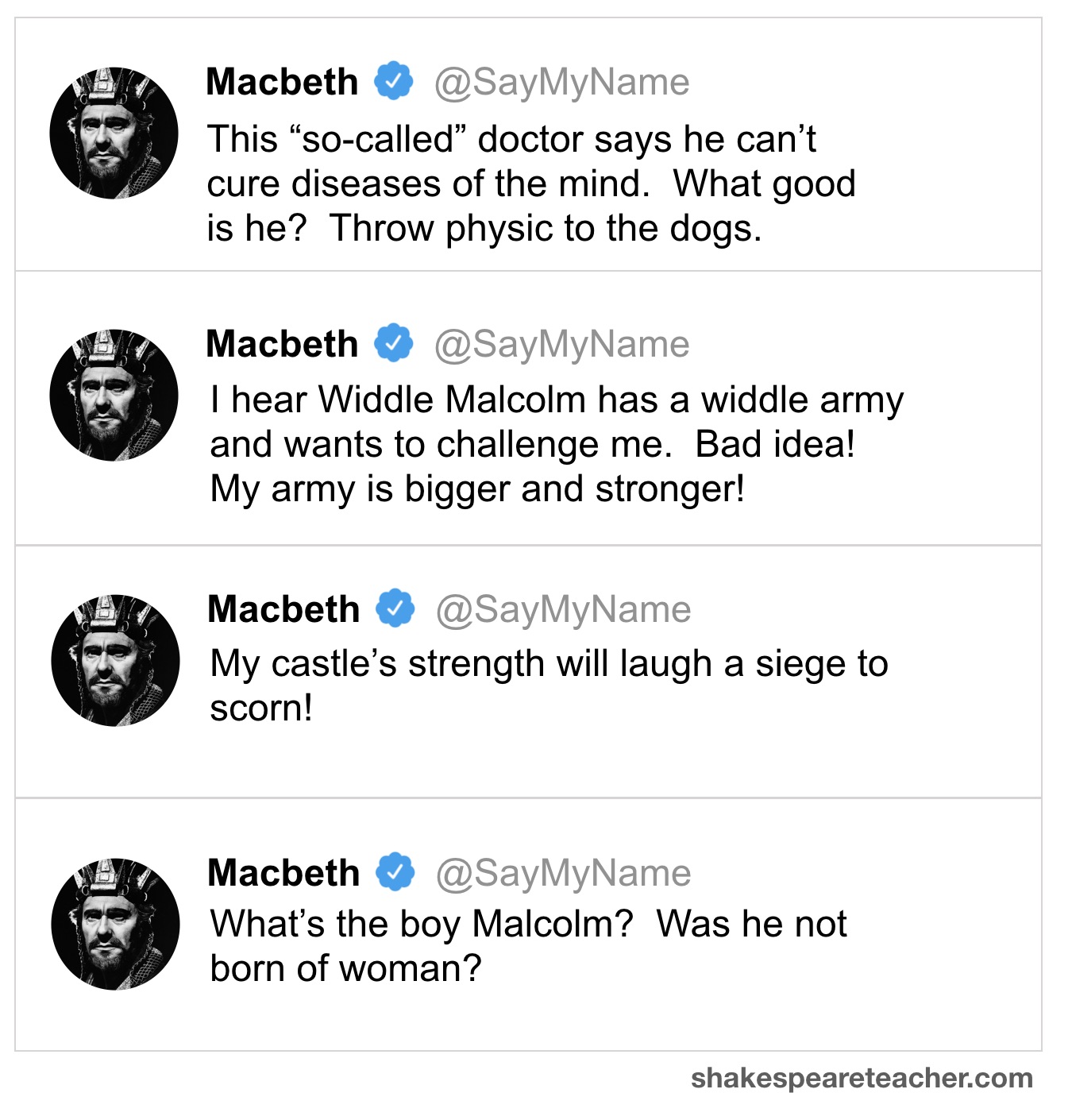

Because Twitter didn’t become well-known until its overhaul in 2006, many people don’t realize that the popular social media platform is actually over a thousand years old.

I was combing through the archives the other day when I found the old Twitter feed of the historical Macbeth. A fascinating primary source document, the daily musings of the king paint a picture of a one-of-a-kind leader, the likes of which we may never see again.

In honor of Shakespeare’s birthday, I am pleased to present a selection of these tweets that may be of interest to fans of the play.

Enjoy!

The feed breaks off there. We can only assume that Macbeth chose that moment to step away from social media and instead turn his attention to the serious business of running Scotland.

But this collection of tweets remains a digital monument to a leader who was clearly way ahead of his time!

The term “nature vs. nurture” is a poetic turn of phrase that refers to an ongoing reexamination of the roles that heredity and environment play in determining who we are as individuals. The expression was popularized in the 19th century by Francis Galton, though the debate and the phrase had been around much longer than his day. In fact, Shakespeare himself juxtaposed the two words in The Tempest, as Prospero describes Caliban thusly:

A devil, a born devil, on whose nature

Nurture can never stick;

Shakespeare was not the first to contrast these two words, but Galton is known to have been a Shakespeare fan, and it seems reasonable to imagine this was his source.

Shakespeare’s plays are filled with models of the intricate workings of human nature, depictions of how individuals are influenced by external factors, and the complicated interplay between the two. As we will soon see, Shakespeare was also an early voice in this conversation, and an often-quoted source by later thinkers as well. Therefore, our Shakespeare Follow-Up will focus on the development of the nature vs. nurture debate from Shakespeare’s time to ours today.

But please note that this is a very large topic, and I’m going to sweep through it rather quickly, so feel free to do your own follow up on any topic here that interests you.

Political philosophers such as Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau are often grouped together as “social contract theorists,” because they presented ideas about how and why humans form societies. But when considering their impact on the nature/nurture question, it’s more illustrative to focus on their differences.

In Leviathan (1651), Thomas Hobbes argued that human beings, existing in a state of nature, are savage and brutal. Therefore, we willingly surrender our autonomy to a sovereign unconditionally in order to gain security from our murderous brethren. John Locke, in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), lays out the idea that we refer to today as tabula rasa, or “the blank slate.” Rather than seeing human beings as being innately evil, as Hobbes does, he sees us as being neither good nor evil naturally, but rather open to influence from our environments. Jean-Jacques Rousseau presents a different view of the natural state of the human in his book Émile (1762). For Rousseau, humans are born innately good, and it is society that corrupts.

Naturally, the choice of which of these three views to adopt will have a profound effect on how a culture views education and child rearing. We can’t control the nature, but we can structure the nurture to make the best use of our understanding of it. If we believe that human beings are born evil, we’ll want to make discipline the backbone of our educational system. If we believe that children are blank slates, we’ll seek to fill those slates with our best models for citizenship and morality. If we believe that our students are innately good, then maybe the best thing we could do would be to just get out of the way and let them explore the world they find themselves in. You can hear echoes of these debates in today’s conversations about education.

In the post-Darwinian era, psychologists began to codify the progression of human development into various stages. The progression was determined by nature, but profoundly impacted by environment. Sigmund Freud described five psycho-sexual stages of development in childhood. The eight psycho-social stages outlined by Erik Erikson were strongly influenced by Freud, but extended to adulthood.

But wait! A lifetime of human progression divided into stages? Why does that sound familiar? Oh right…

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel,

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lin’d,

With eyes severe, and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side,

His youthful hose well sav’d, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

It seems that Jacques in As You Like It was on the right track, centuries ahead of his time. Freud famously wrote about Hamlet, and Erikson even cites Shakespeare’s “ages of man” in his 1962 article “Youth: Fidelity and Diversity,” which also provides an in-depth discussion of Hamlet.

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) developed a set of four stages of cognitive development that have been profoundly influential in our understanding of human nature. Piaget believed that these stages developed naturally, and that new levels of learning become possible at each stage. Score one point for nature! Lev Vygotsky (1896 – 1934) built on these ideas, but demonstrated that learning could actually encourage cognitive development. There is a zone between what students are capable of doing on their own and what they can do in an environment that includes guidance and collaboration. Stretching into this zone can assist children in progressing developmentally. There’s one point for nurture, and it’s a tie game.

In fact, it will always be a tie game. Everyone agrees that both nature and nurture are significant, and we can argue about various degrees. Noam Chomsky (1928 – ) revolutionized the field of linguistics by describing, in Syntactic Structures (1957), the innate ability of the human brain to acquire language. This was a challenge to the behaviorist philosophy that was dominant at the time. In Frames of Mind (1983), Howard Gardner describes a system of multiple intelligences that different people seem to possess in different measures. The rise of theories such as Chomsky’s and Gardner’s would seem to move the needle towards nature, but the fact that they continue to influence our educational practices demonstrate the importance of nurture in the equation all the more powerfully.

Shakespeare, of course, didn’t know any of this. Nevertheless, his understanding of the complex interplay between nature and nurture was nuanced enough for him to create models that still have us debating the actions and motivations of fictional characters as though they were real people. Why, for example, does Macbeth kill Duncan? Is it because he’s ambitious? Or does he succumb to pressure from his wife? If it’s the former, would he have done so without prompting from the witches? And if it’s the latter, what elements of his nature make him susceptible to his wife’s influence?

I give up. What do you think, Lady Macbeth?

Glamis thou art, and Cawdor; and shalt be

What thou art promis’d. Yet do I fear thy nature;

It is too full o’ the milk of human kindness

To catch the nearest way; thou wouldst be great,

Art not without ambition, but without

The illness should attend it; what thou wouldst highly,

That thou wouldst holily; wouldst not play false,

And yet wouldst wrongly win; thou’dst have, great Glamis,

That which cries, ‘Thus thou must do, if thou have it;’

And that which rather thou dost fear to do

Than wishest should be undone. Hie thee hither,

That I may pour my spirits in thine ear,

And chastise with the valour of my tongue

All that impedes thee from the golden round,

Which fate and metaphysical aid doth seem

To have thee crown’d withal.

A lot of these Follow-Ups are about how much Shakespeare didn’t know. This one is about how much he still has to teach us.

Across the United States, education is undergoing a sea-change (into something rich and strange) surrounding the adoption of something called the Common Core State Standards.

Standards are simply a list of what students should be able to do by the end of each grade. Traditionally, these have been defined by states, with a requirement for them to do so by the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. States still define their own standards, but, in an unprecedented act of coordination, 45 states (plus the District of Columbia and a few of the territories) have adopted the Common Core as their state standards. Full adoption has been targeted for next year, though New York has started phasing in significant portions of it this year.

Love it or hate it, the Common Core represents a new direction in pedagogical thinking, both qualitatively and quantitatively. Personally, I think the Common Core standards are a lot better than the existing New York State Standards, but we’re going to have to suffer through a difficult transition period before we can reap the benefits of that improvement. Right now is probably the most difficult time, as we have to deal with students who are not starting on what the new structure defines as grade-level, a lack of Common Core-aligned teaching materials, and uncertainty surrounding precisely how these new standards will be assessed. May you live in interesting times.

As with anything new and complex, there are going to be a number of misconceptions floating around about it. One of the most prevalent I’ve seen is that the Common Core eliminates (or at least de-emphasizes) literature, in favor of informational texts. In particular, many are convinced that Shakespeare will be replaced entirely by non-fiction, as public education descends into a Dickensian nightmare of Shakespeare-deprived conformity and standardization.

In fact, Shakespeare is mandated by the Common Core.

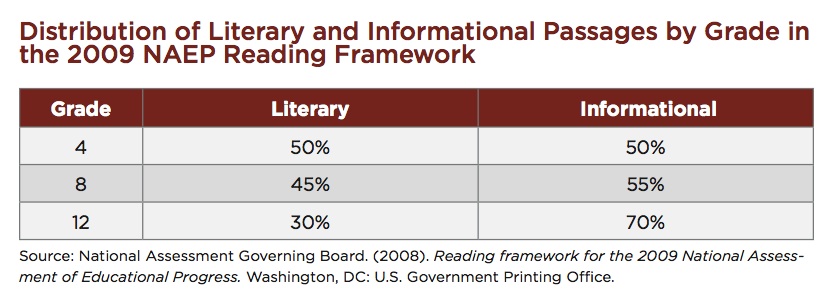

The confusion seems to stem from a chart that appears on page 5 of the English Language Arts Standards document, outlining the percentages of literary vs. informational texts included in the National Assessment of Educational Progress:

(Click for a larger image.)

The Common Core is explicit about aligning curricula with this framework, but it is just as explicit about how that alignment should be distributed:

Fulfilling the Standards for 6–12 ELA requires much greater attention to a specific category of informational text—literary nonfiction—than has been traditional. Because the ELA classroom must focus on literature (stories, drama, and poetry) as well as literary nonfiction, a great deal of informational reading in grades 6–12 must take place in other classes if the NAEP assessment framework is to be matched instructionally.

So, despite the canard that high-school English classes will only be allowed to teach literature 30% of the time, the 70% informational text requirement refers to the entirety of student reading across the curriculum. Given that one of the major shifts is an increase in reading and writing in the content areas, the ratio makes sense.

Let’s say that, over the course of a particular unit, a high-school English teacher is assigning 3 literary texts and 1 informational text. That means that (text length aside) students are reading 75% literature in English class. And if this is the only reading the students are doing, then they are reading 75% literature overall. But now imagine that, during the same timeframe, they are also reading 2 informational texts in social studies, 2 informational texts in science, and 2 informational texts in all of their other classes combined. They are still reading 75% literature in English class, but this now represents 30% of their reading overall.

And, far from being lost in the informational-text shuffle, Shakespeare now becomes the man of the hour. As the only author explicitly required by the Common Core, Shakespeare must be taught in grades 11 and 12 (see page 38, right column, Standards 4 and 7). Shakespeare is also included in the recommended texts for grades 9 and 10 (see page 58, left column, center). And Shakespeare is not excluded for younger students either, as the standards outline only the minimum of what must be taught in each grade. The Common Core does stress using authentic texts, so updated language versions of Shakespeare would be frowned upon, but that’s actually an adjustment I can get behind.

There is a lot of controversy surrounding the Common Core, and a lot of objections surrounding the new changes. Some of these objections are legitimate, and some are not. I look forward to continuing that conversation as the implementation develops. But rest assured that Shakespeare isn’t going anywhere.

In Shakespeare’s time, people did not go to “see” a play; they went to “hear” a play. Which Shakespeare play would you like to hear?

A few months ago, I wrote a post about my Shakespeare addiction that referenced the Caedmon audio production of As You Like It. Regular readers of the blog know well the extent of this addiction, but what they may not know is the degree to which that addiction includes audio productions of Shakespeare. Most people organize their mp3 playlists with different genres of music plus one “Spoken Word” category. My iPhone has a “Music” playlist, with various Spoken Word sub-genres, including several playlists of performances of Shakespeare. Given the hours upon hours I have spent listening to these productions, I am now pleased to share with you my ten very favorite selections.

Now, if this is your thing, you really need to get The Complete Arkangel Shakespeare. This is a breathtaking collection of top-quality productions of each of Shakespeare’s plays, directed by Clive Brill and with original music by Dominique Le Gendre. The advantage of buying the set is that you will then have the option to listen to any title you choose. But if you’re not ready to make that kind of investment into the eclectic world of Shakespeare audio, I can give you my own top picks so you can get your feet wet before diving into the deep end of the pool.

Standard disclaimers apply. These are based on my own preferences, which are always subject to change. I based my rankings on writing, acting, directing, production, and music. I limited myself to modern productions only, so you won’t find Paul Robeson or Orson Welles on the list. And I’m sure there are many excellent productions I haven’t listened to. Basically, these are the ten audio productions of Shakespeare I find myself returning to again and again.

And, in keeping with tradition, my top ten list will have twenty entries. Enjoy!

Directed by Glyn Dearman; Starring Sir John Gielgud (Lear), Kenneth Branagh (Edmund), Emma Thompson (Cordelia), Derek Jacobi (France), Bob Hoskins (Oswald), Judi Dench (Goneril), Michael Williams (Fool), and Richard Briers (Gloucester).

This, to me, is the definitive audio Lear. Gielgud takes a larger-than-life character and truly brings out his humanity. An all-star cast delivers solid performances across the ensemble. This is Shakespeare the way it was meant to be performed.

Vanessa Redgrave as Rosalind gives one of the greatest audio performances I’ve ever heard. If you’re a fan of the play, or even if you’re not, you owe it to yourself to hear this amazing production.

Starring Kenneth Branagh (Richard III), Celia Imrie (Queen Elizabeth), Bruce Alexander (Edward IV), Michael Maloney (Clarence), John Shrapnel (Hastings), Stella Gonet (Anne), Jamie Glover (Richmond), and Nicholas Farrell (Buckingham).

I wouldn’t really have thought of Branagh for the hunchbacked villain, but he does a great job leading a top-notch cast in performing Shakespeare’s classic history play. I never really knew how much was going on in this play until I heard this production.

Starring Michael Feast (Julius Caesar), John Bowe (Brutus), Adrian Lester (Mark Antony), Geoffrey Whitehead (Cassius), Estelle Kohler (Portia), and Jonathan Tayler (Octavius).

I can listen to this one again and again. The exchanges between Bowe’s Brutus and Whitehead’s Cassius are electric, and Marc Antony’s powerful monologues are explosive in Lester’s more-than-capable hands.

5. The Comedy of Errors (Arkangel)

Starring David Tennant (Antipholus of Syracuse), Brendan Coyle (Antipholus of Ephesus), Alan Cox (Dromio of Syracuse), Jason O’Mara (Dromio of Ephesus), Niamh Cusack (Adriana), Sorcha Cusack (Luciana), and Trevor Peacock (Egeon).

Along his path to directing the canon, Clive Brill has a lot of fun with Shakespeare’s only slapstick comedy. Silly sound effects and comical music underscore fantastic comic performances by a brilliant cast. Remember, dying is easy; Comedy‘s hard.

Starring Michael Feast (King John), Eileen Atkins (Constance), Michael Maloney (Bastard), Geoffrey Whitehead (Phillip), Trevor Peacock (Hubert), Bill Nighy (Pandulph), and Margaret Robertson (Elinor).

Michael Maloney steals this particular show, as the Bastard often does in King John. But strong performances across the cast have the power to churn the blood and tug a few heartstrings as well.

There are a number of audio Macbeths to choose from, but I give Anthony Quayle pride of place. Mood-enhancing sound effects and strong performances across the board make this production the Macbeth of choice.

Starring Hugh Quarshie (Othello), Anton Lesser (Iago), Emma Fielding (Desdemona).

Lesser’s edgy voice creates a dangerous Iago, who provokes a genuine sense of menace. Quarshie’s passionate Othello makes for a worthy tragic figure. Together, the two performances leave us with an unforgettable audio experience.

Directed by David Timson; Starring Samuel West as Henry V.

This is a stirring and creative production of Henry V. Vibrant interpretations of even the minor characters make for a consistently interesting and entertaining presentation of the well-beloved history.

Starring Niamh Cusak (Rosalind), Stephen Mangan (Orlando), Gerard Murphy (Jaques), Clarence Smith (Touchstone), and Victoria Hamilton (Celia).

This is a really great audio production of the play. I rated the other version much higher, but I actually prefer Dominique Le Gendre’s music in this one. And for As You Like It, the music is no insignificant character.

11. Measure for Measure (Arkangel)

Starring Roger Allan (Duke), Simon Russell Beale (Angelo), Stella Gonet (Isabella), Jonathan Firth (Claudio), and Stephen Mangan (Lucio).

Here’s another one I keep revisiting. Beale and Gonet create sparks as Angelo and Isabella, Mangan is brilliant as Lucio, and Allan’s Duke never lets you forget who’s in charge. I think I want to go listen to this one right now.

Starring Paul Scofield (Lear), Alec McCowen (Gloucester), Kenneth Branagh (Fool), David Burke (Kent), Harriet Walter (Goneril), Emilia Fox (Cordelia), Sara Kestelman (Regan), Richard McCabe (Edgar), and Toby Stephens (Edmund).

Okay, so Paul Scofield as Lear should be enough, right? But he is supported by a great ensemble cast in a well-directed version of one of the greatest plays ever written. Check it out!

Starring Ian McKellen (Prospero), Scott Handy (Ariel), Emilia Fox (Miranda), Neville Jason (Antonio), Benedict Cumberbatch (Ferdinand), and Ben Onwukwe (Caliban).

Okay, so Ian McKellen as Prospero should be enough, right? But this is another high-quality Naxos masterpiece – a must-have for Shakespeare audio collectors.

14. Henry IV, Part One (Arkangel)

Starring Jamie Glover (Hal), Julian Glover (Henry IV), Alan Cox (Hotspur), and Richard Griffiths (Falstaff).

I really love this play, and the Arkangel production does it great justice. Griffiths creates a Falstaff with his voice that has the power to rival his stage counterparts. Each scene in this production is like a little gift-wrapped present.

Anton Lesser is the man! This time, he lends his distinctive voice to the Melancholy Dane, striking just the right balance between contemplative and bitter, between witty and mad. There are certainly other audio Hamlets, but Lesser is greater!

16. A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Naxos)

Starring Warren Mitchell (Bottom), Michael Maloney (Oberon), Sarah Woodward (Titania), Jack Ellis (Theseus), Benjamin Soames (Lysander), Jamie Glover (Demetrius), Cathy Sara (Hermia), Emily Raymond (Helena), and Ian Hughes (Puck).

Again, I have several versions of the Dream to choose from, but I think I’ll take Naxos for the win. I’ve heard these words so many times, it’s an impressive production that can still make me laugh at them.

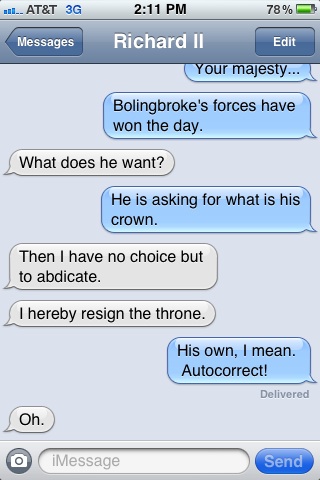

Starring Rupert Graves (Richard II), Julian Glover (Bolingbroke), and John Wood (John of Gaunt).

Let’s talk of Graves. (See what I did there?) He gives an outstanding performance as Richard, which is important, because – let’s face it – he does tend to go on a little.

18. Henry VI, Part Three (Arkangel)

Starring David Tennant (Henry VI), Kelly Hunter (Margaret), Clive Merrison (York), Stephen Boxer (Edward), John Bowe (Warwick), and David Troughton (Richard).

This is the beauty of the Arkangel series. You can listen to any play, any act, any scene you like. And sometimes, you just really need to hear the “paper crown” scene. When that day comes for you, this is the recording you’ll want to have.

19. Romeo and Juliet (Arkangel)

Starring Joseph Fiennes (Romeo), Maria Miles (Juliet), and Elizabeth Spriggs (Nurse).

Dominique Le Gendre’s love theme for this production becomes the theme song for the entire Arkangel series. Fiennes and Miles are wonderful, as you knew they would be. When you want to hear this play, hear this version.

Starring Stella Gonet (Viola), Jonathan Keeble (Orsino), Jane Whittenshaw (Maria), Malcolm Sinclair (Andrew), David Timson (Feste), Lucy Whybrow (Olivia), Christopher Godwin (Malvolio), and Gerard Murphy (Toby).

Well, what can I say, this is my twentieth favorite. But it’s the best of all of the Twelfth Night productions I own, and it’s a great presentation of a fun play, so why not give it a listen?

With rumors of an Arrested Development movie in the works, contrary to earlier rumors that it was not, it seems like a good time to look back at the amazing TV series America discovered just a bit too late. As critics and fans appropriately sing the praises of the brilliant creative team being reassembled, I thought I’d say a few words about the spiritual grandfather of the series, without whom none of this would have been possible: Sigmund Freud. My intent here will not be to add a layer of Freudian analysis on top of the show, but rather to demonstrate the strong Freudian currents that already run throughout the series. If that appeals to you, just lie back on the couch, and read on!

Michael Bluth is established as the central character in the opening credits, and all of the other characters are defined by their relationship to him. The family, therefore, represents Michael’s psyche in all of its facets. Michael has three siblings, who represent his id, ego, and superego. Older brother G.O.B. is the id, seeking pleasure and avoiding responsibility at every turn. He often wins the things Michael wants by pursuing them without any of Michael’s second-guessing. Sister Lindsay represents the ego, constantly refashioning her definition of self to gain the attention and approval of others. It is no coincidence that she is framed as Michael’s twin. Younger brother Buster is the superego, living his life by others’ rules and in constant fear of his own independence. His obvious issues reflect Michael’s more subtle inability to break free from his family. But Michael can no more escape them than he can distance himself from his own psyche; they are a part of him.

Even in the series finale, when Michael finally fulfills his wish to be free of them, he winds up face to face with the one person he most wants to avoid, his father. Michael’s number one driving force throughout the series is the very Freudian desire to supplant his father: he wants to replace his father as the president of the Bluth Company, and he wants to be a better father to his son George-Michael than George Sr. was to him. (The names here are no coincidence; George-Michael combines the names of his father and grandfather, and they are to live on through him. Does George Sr. have another grandchild who can carry on his legacy? Maeby.) George Sr. is a very dominant figure to this family – powerful, controlling, sexually voracious. He also has an alter ego in his identical twin brother Oscar, who is carefree and nurturing. Note that Oscar is George Sr.’s middle name as well. It is built into the show’s premise that one of them must be imprisoned at all times. In one episode, they are both out of prison, and they fight. Being twins, neither is able to defeat the other. This represents the duality of Michael’s father image.

Just as George Sr. is an archetypical father figure, Lucille is a controlling mother right out of the Freudian playbook. She is the one who pulls all of the strings, and she’s not above pitting her children against each other as a power play. When Buster (Michael’s superego) disobeys her just once, he literally has a body part bitten off by a “loose seal,” a deliberate play on Mom’s name, justifying his castration anxiety. When Buster first dates, it’s a mature woman named Lucille. Again, Buster’s obvious issues highlight the dynamics of the family as a whole. A recurring theme with Buster is having borderline-incestuous overtones in his relationship with his mother. In fact, incest is much more of a theme on this show than one would normally expect on network television, particularly the tension between George-Michael and his cousin Maeby, but in several other places as well. Lucille has an affair with her brother-in-law. George Sr. and G.O.B. independently see a prostitute that Michael suspects might be his sister (and who is conspicuously played by the actor’s sister). When Lindsay finds out she’s adopted, the first thing she does is make a pass at Michael.

Tobias, as an in-law, is outside of this system of Michael’s psyche, but is close enough to it to provide commentary. He serves as the voice of the analyst (or therapist, or… whatever), and his tidbits of psychoanalysis are all Freud. But Tobias himself is the most overtly Freudian character of them all, as he constantly expresses his repressed homosexual desires through his layered speech patterns. Barry Zuckercorn, who (unlike Tobias) acts on his desires and lies about it, often makes Freudian slips revealing his activity, due to a subconscious desire to be found out. More subtle examples of subconscious feelings revealing themselves through language patterns are found throughout the series, as with Michael’s inability to remember Anne’s name masking his hostility towards her or with George-Michael’s talking about Maeby and inadvertently revealing his lustful thoughts.

One of Freud’s major contributions was in demonstrating how early experiences in our lives can affect the people we will later become, and Arrested Development keeps coming back to this theme. The “lessons” George Sr. teaches his children return to them repeatedly later in life. Michael’s affinity for playacting the role of a lawyer can be traced back to a role he had in a school play. One can only imagine the memories being formed by the kids who acted in the warden’s play. The “Boyfights” that Michael and G.O.B. engaged in as children helped form the relationship they have as adults… to the degree that they have become adults.

And here we have one of the most important themes of the series, found in the very title. Freud originated the concept of stage-based development, which would later influence such thinkers as Erikson and Piaget. If one’s development is “arrested” it means that he or she does not normally move into the next stage at the appropriate time. In the series Arrested Development, adult characters often display juvenile characteristics and continue to play out family dynamics they should have long outgrown, again demonstrating how early experiences can be formative in deciding who we will be later in life. Freud would have been proud.

You may notice that, in all of my discussion of Freud, I have avoided discussing some of the more phallic imagery in the show. But sometimes a banana stand is just a banana stand.

This is the fourth in a five-part series of Shakespeare Lipograms. For my fourth lipogram, I have chosen to summarize a Tragedy, Hamlet, using “O” as the only vowel.

Enjoy!

Two on post show Old Crown Lord’s Ghost to Bosom Cohort, who looks on spook from top to bottom. Bosom Cohort knows to show Ghost to Forlorn Son. Forlorn Son dons low moods, won’t show known Crown Lord props. Forlorn Son broods:

“O God! O God! How worlds rot! How’s Pop forgot so soon? Not two months lost, no, not so, not two. So good to comfort Mom. Now – oh no! – to go from joy to sorrow. Crown Lord mocks protocol to hook control of stronghold so pronto to follow Pop’s drop-off. Took Mom for consort too soon, too soon. O, Mom shows so hollow! So not cool.”

Cross Hotblood told Moon Tot not to grow too fond of Forlorn Son, for Moon Tot’s born too lowbrow to show Forlorn Son how to don crowns. Top Lord told Cross Hotblood world-won words: “Son, do not borrow – not from, nor to – for to do so oft shows not gold nor cohort to follow.” Top Lord told Moon Tot not to grow too fond of Forlorn Son too, for boys’ vows oft show too hollow. Moon Tot conforms.

Bosom Cohort shows Ghost to Forlorn Son. Ghost told Forlorn Son to follow. Ghost shows Forlorn Son books of sorrow, from Ghost’s own bro, Crown Lord. “Son, for honor, go knock on Crown Lord’s door, who took to rob Pop of crown, of growth, of consort – lost! Do not scold Consort Mom. Now go!” Forlorn Son opts to go from low moods to mock fool.

Crown Lord now longs to know roots of Forlorn Son’s odd moods. Top Lord shows Crown Lord how Forlorn Son’s soft spot for Moon Tot grows odd moods. Consort Mom looks to how Forlorn Son sobs for Pop for roots of Forlorn Son’s odd moods. Forlorn Son shows two old school cohorts (who snoop for Crown Lord) how loss of Pop’s crown grows odd moods. Crown Lord knows not of Ghost’s words. Top Lord shows Show Troop to Forlorn Son. Show Troop shows off for Forlorn Son. Forlorn Son shows Show Troop how to form shows to work on crooks.

Crown Lord snoops on Forlorn Son. Top Lord snoops too. Forlorn Son broods solo: “To go on, or not to go on? Moot. To drop off? To nod down to stop lots of wrongs? Or to go to post-worlds of doom? No! Horror works on lots of cold-foot poltroons. So, do go on. Do go on. Soft! How now, Moon Tot?” Moon Tot confronts Forlorn Son. Forlorn Son scorns Moon Tot to go to God’s fold.

Crown Lord cottons to go to Show Troop’s show “Knock Off.” Crown Lord holds no joy to look on Show Troop’s show. Crown Lord opts to go, so Forlorn Son now knows. For Crown Lord to go off shows proof of Ghost Pop’s word. Top Lord told Forlorn Son to go to Consort Mom’s room. Forlorn Son looks on Crown Lord’s stoop to roods. Forlorn Son won’t knock off Crown Lord to go to God. Forlorn Son holds on. Forlorn Son shocks Consort Mom. Top Lord snoops. Forlorn Son swords… Crown Lord? No, Top Lord. Oops. Forlorn Son scolds Consort Mom, so Ghost Pop shows to stop Forlorn Son short.

Crown Lord books Forlorn Son’s two old school cohorts to convoy Forlorn Son to London. Forlorn Son looks on Oslo Lord’s troops. Oslo Lord’s honor grows on Forlorn Son. Cross Hotblood shows to look for Crown Lord’s blood. Lots of townsfolk show for Cross Hotblood. Crown Lord knows to look to Forlorn Son for Cross Hotblood’s honor. Cross Hotblood looks on Moon Tot, who shows odd moods. Cross Hotblood vows to knock off Forlorn Son. Moon Tot drowns.

Forlorn Son bolts both old school cohorts. Morons. Forlorn Son shows tomb-lot to Bosom Cohort. Two Tomb-lot Clowns fool to Forlorn Son. Both show Old Fool’s crown to Forlorn Son, who broods: “Forsooth, poor Old Fool. Known to stronghold folks, Bosom Cohort. How oft Old Fool told stronghold folks how to roll. How doom follows Old Fool now. Go to Mom’s room, Old Fool, show how fools rot. Mom won’t howl. Bosom Cohort, follow. Lords or lowbrows both go to worms’ food, or for chocks to stop hooch pots. Soft! Crown Lord shows!” Forlorn Son looks on Crown Lord, who comforts Consort Mom. Cross Hotblood sobs to go down to Moon Tot’s tomb. Forlorn Son hops down to confront Cross Hotblood. Both opt for swords.

Cross Hotblood blots hot sword. Crown Lord blots strong port. Both form doom for Forlorn Son. Forlorn Son shows. Forlorn Son bows to Cross Hotblood for Top Lord boo-boo. Both hold swords for sport row. Both go. Crown Lord holds port to honor Forlorn Son. Forlorn Son longs not for port. Consort Mom downs strong port. Oops.

Forlorn Son shows strong to notch two blows on Cross Hotblood. Cross Hotblood swords Forlorn Son. Ow! Forlorn Son swords Cross Hotblood, who drops hot sword. Forlorn Son now holds Cross Hotblood’s hot sword. Cross Hotblood now holds Forlorn Son’s cold sword. Forlorn Son swords Cross Hotblood, who knows both now look on doom. Consort Mom drops from strong port. Cross Hotblood told Forlorn Son of hot sword, of strong port, of Crown Lord’s non-honor. Forlorn Son swords Crown Lord, floods Crown Lord’s gob of strong port. “Follow Mom!” Crown Lord drops off.

Forlorn Son looks to Cross Hotblood. Both smooth off storms of loss for honor. Cross Hotblood drops off. Forlorn Son stoops down. Forlorn Son sponsors Oslo Lord to hold crown now. Forlorn Son drops off. Bosom Cohort croons: “Good morrow, good crown lord’s son. Go to God on good songs.” London Lord shows to post word of Forlorn Son’s two old school cohorts lost. Oslo Lord shows, now top dog. Both sob for loss. Oslo Lord drops word for troops to go shoot.

I subscribe to a service called “SiteMeter” which allows me to see a limited amount of information about my visitors. One thing that I can see is if someone finds my site via a Google search. Recently, I’ve had a number of hits from people looking to find out about living descendants of King Henry VIII. My site isn’t really about that, but I thought I’d provide an answer anyway, as a public service.

There are no living descendants of King Henry VIII.

Henry’s father, King Henry VII, had four offspring who lived past childhood: Arthur, Margaret, Henry, and Mary. Arthur was always expected to be the next king, but he died in 1502. When Henry VII died in 1509, the kingdom was passed to his younger son, crowned Henry VIII.

Henry VIII had four known living offspring from four different women. His first wife, Catherine of Arragon, gave him a daughter, Mary (born 1516). He had an illegitimate son, Henry FitzRoy (born 1519), with his mistress Elizabeth Blount. His second wife, Ann Boleyn, had a daughter Elizabeth (born 1533). His third wife, Jane Seymour, had a son, Edward (born 1537). Henry VIII would have three more wives, but no more children to carry on his line. And as we shall see, none of his four branches would bear fruit.

Henry FitzRoy died in 1536, while his father was still alive.

When Henry VIII died in 1547, young Edward became King Edward VI, but died in 1553 with no heir. He was 15 years old. That was the end of Henry’s Y chromosome. But what about the daughters?

There was a brief reign by Lady Jane Grey (not a descendant of Henry VIII, but a granddaughter of his sister Mary) and then Henry VIII’s daughter Mary took the throne as Queen Mary I of England. You may know her as Bloody Mary.

(Don’t confuse either Mary with Mary Queen of Scots, who was yet a third Mary. She is a descendant of Henry VIII’s sister Margaret. We’ll come back to her in a bit.)

Mary I of England died in 1558 with no offspring, leaving the country in the capable hands of her sister Elizabeth. During the 45-year-long reign of Queen Elizabeth I, we saw a new Golden Age which included the rise of Shakespeare and Sir Francis Bacon. But alas, we saw no heir. Elizabeth died in 1603, ending her father’s biological legacy forever.

The crown then passed to the son of Mary Queen of Scots, who was James VI of Scotland at the time. He became King James I of England. And Shakespeare quickly began work on Macbeth. Note that the British monarchy even today can be traced back to King Henry VII, the father of King Henry VIII.

But King Henry VIII himself has no known living descendants.

I hope this was helpful for at least some of you. For the rest of you, expect a new Conundrum tomorrow.

UPDATE: An anagram version of the answer!